- Home

- Gilling, Tom

Dreamland Page 2

Dreamland Read online

Page 2

The main room was long and low and narrow. Rusty dance cages stretched from floor to ceiling. The décor—or what Nick could see of it in the crepuscular strobe lighting—evoked an S&M dungeon, mock-stone walls adorned with whips and chains and leather masks. The whole room pulsed with sound: ‘Temptation’, by New Order—one of Nick’s favourite songs, and incidentally one of Carolyn’s too. (Which was ironic, Nick couldn’t help thinking, since of all the people he knew, none was less susceptible to temptation than Carolyn.) The Crypt was a goldmine, as notorious for its stratospheric bar prices and strategic lack of airconditioning as for its regular drug raids and fire safety violations.

Nick looked about for Danny, or at least for the still point in the crowd that might imply his presence.

As the only son of Harry Grogan, AO, billionaire founder and chairman-for-life of Grogan Constructions, Danny would have been a celebrity even without the Crypt.

From its beginnings as a subcontractor in the outer western suburbs of Sydney, Grogan Constructions had turned itself into one of the powerhouses of the Australian building industry— the developer, manager and majority owner of the Dreamland hotel on the north shore of Sydney Harbour. A Byzantine network of family trusts owned more than half the company and controlled nearly 75 percent of the voting stock. Analysts attributed the lion’s share of its billion-dollar valuation to faith in Harry Grogan himself, whose genius in staring down his creditors and pulling the company back from the brink of bankruptcy was the stuff of stock market legend.

The Crypt was a symbol of Danny’s rejection of the future his father had planned for him, the rejection of his inheritance. By the age of twenty-nine, playboy Danny was supposed to have metamorphosed, under the inspirational example of his father and the shadowy cabal of American executives who ran the company, into hard-headed Daniel, heir apparent and future CEO of Grogan Constructions. Danny was the dynasty in waiting, and he didn’t want any part of it. Meanwhile the Crypt had made him a rich man—and a staple of the tabloids and weekly magazines.

A year ago Danny had got himself on the cover of Who Weekly, dancing with Dannii Minogue. Nick remembered the cheesy cover line: DANNY HITS THE CRYPT WITH DANNII. There were hints in the article that they were—or were about to become—an item, although Dannii’s people soon scotched that. Danny had spoken to Nick just as the next week’s issue (DANNY AND DANNII— IT’S OVER) hit the newsstands. It had been a fiction from the start but Danny played it for all it was worth. He was coolly disparaging of his media image but at the same time in thrall to it: as if some part of him actually believed the rubbish that was written about him. And at some level, of course, the rubbish was true. The more they wrote about Danny’s glamour and notoriety, the more glamorous and notorious he became.

At the bar Nick discovered that he didn’t have enough for a bottle of Steinlager and had to settle for tomato juice. Glancing at the angled mirror above the bar, he finally caught sight of Danny. He had his arm around a wasted-looking girl—she couldn’t have been more than seventeen—who was trying to drag him away.

Nick called out his name.

Danny turned around. He was high on something, Nick realised. Danny stared at him for a few seconds. He seemed to have trouble focusing and Nick wasn’t sure Danny recognised him. Finally he murmured, ‘Nick.’

‘Thanks for putting my name on the door.’

Danny nodded vaguely.

‘I was being sarcastic,’ said Nick. ‘Your bouncer wouldn’t let me in.’

Danny kept staring, and shifting his focus. Behind him, Nick recognised a couple of faces from St Dominic’s. He couldn’t put a name to either of them but he thought he remembered the taller man as one of Glazer’s chief tormentors. St Dominic’s didn’t have the kudos or the sporting heritage of most of its rivals but made up for it by charging the highest fees. The school had been named after St Dominic (1170–1221), founder of the Dominican order and patron saint of astronomers, but a more plausible guardian, Nick had come to realise, was his namesake St Dominic Savio (1842–1857), patron saint of juvenile delinquents. There was something about the dynamics of power and wealth at St Dominic’s that Nick had never been able to understand because he was excluded from it. It wasn’t the immorality of privilege; it was the amorality of privilege—a sense of entitlement that belonged, in some macabre way, to both Glazer and his schoolboy persecutors. This wake was the perfect expression of that amorality—a send-off for a dead man that nobody could remember liking, in a converted church where the bouncers sold drugs to under-age dancers.

The girl was still trying to pull Danny away. She shot a fierce glance at Nick and said, ‘Danny’s sick.’

He didn’t look sick to Nick. He looked frightened and disoriented. ‘Danny,’ said Nick. ‘Are you all right?’

‘He’s fine,’ the girl insisted.

‘You just told me he was sick.’

‘He is sick. I’m taking him home—aren’t I, Danny?’

Danny didn’t answer.

Nick put a hand on his shoulder. ‘There was something you wanted to tell me.’ He didn’t know whether that was true or not. Information came to Danny: because of who he was, because of who his father was. Sometimes he gave Nick a story to see what he would do with it. Maybe that was why Danny had invited him here. Maybe it was why Nick had come. But Danny could hardly speak.

‘You should get him home,’ said Nick.

‘Yeah,’ the girl said. ‘That’s where we’re going, isn’t it Danny?’

She kept looking for his consent although it seemed to Nick that in the state Danny was in, he would have consented to anything.

‘Call me,’ said Nick, although even as he said it he knew Danny wasn’t going to.

A taxi pulled up outside the club and disgorged three girls onto the pavement. Nick thought about getting in, then changed his mind. A walk would do him good.

He wandered past the cafes and pubs and pizza shops and turned left into Crown Street. In a cobbled lane near the primary school, a metallic blue Audi TT coupe sat among the overflowing wheelie bins—not so much parked as abandoned. A sign beside it said ‘No Standing’. Even without its customised numberplate, CR1PT, Nick would have recognised the car as Danny Grogan’s.

The Audi’s offside headlight was broken and the wing panel and passenger door were dented. The engine was still warm. Nick looked through the passenger window. A small sequined handbag was lying on the seat. The glove box door gaped open, but the glove box was empty.

It was a ten-minute walk from here to the Crypt. Yet Danny had his own private parking spot at the back of the club. Why would he have got out and walked, Nick wondered. He stared at the handbag on the passenger seat. Either Danny hadn’t trusted himself to drive—or someone else hadn’t.

Nick crossed the road and lit a cigarette and kept walking. He thought about what had happened at the club. He’d turned up because Danny had implied there might be something in it for him—but what? Danny was always good for a tip-off, a piece of second-hand underworld gossip worth a few paragraphs on page three of the Star. But in the back of Nick’s mind there lurked a hope of something bigger: the story, the real story behind the fire that claimed three lives and made Harry Grogan a millionaire. If Nick was honest about it, that was the reason he couldn’t let go of Danny. So tonight wasn’t going to be the night. There would be other nights, other let-downs. It was a story worth waiting for.

A nearly full moon hung over the city skyline. Nick was conscious of being followed—not by a person but by a dog. The dog was sitting—or rather, crouching—on the pavement, about twenty metres behind him. Nick had noticed it sitting forlornly under a tree in Prince Alfred Park. It looked like a greyhound. That is, it had the shape of a greyhound but not, somehow, the elastic quiver that a greyhound ought to have. They had locked eyes and the animal had taken this brief intimacy as an invitation to accompany Nick to wherever he might be going. Nick faced the dog and tried to shoo it away but the greyhound just cocked its

head and stayed where it was. Nick glanced at his watch. It was after midnight. He turned the corner into Abercrombie Street and kept on walking.

For six weeks—ever since he’d come home to find Carolyn typing her reasons for splitting up on his laptop—Nick had been sleeping in the spare bedroom of a crumbling Victorian terrace in Abercrombie Street, Chippendale. The house belonged to a fellow subeditor at the Star, Sally Grabowsky. Sally was divorced and had a three-year-old, Jessica, who liked Nick but was confused as to his status in the household, referring to him usually as ‘Nick’ but sometimes, disconcertingly, as ‘Daddy’. Her real daddy, according to the solicitor’s last reported sighting, was working on a prawn trawler somewhere in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Nick lay in bed, half-listening to the ritual early-morning negotiation between mother and daughter over what Jess could have for breakfast if she promised to feed herself. Children had never actually been a subject of conversation with Carolyn, though Nick suspected he had the makings of a good father. Sharing a house with Jess had reinforced this impression. It surprised him how much he could enjoy talking nonsense with someone else’s three-year-old.

He thought about Danny Grogan’s car and wondered whether it was still where Danny had left it. Chances were it had been towed away and was sitting in a pound somewhere. According to a gossip column Nick remembered reading, in three years Danny Grogan had racked up more than half the cost of his Audi TT in parking fines.

It was 6.55 a.m. on the first day of the new year and the sky behind the cheap venetian blind was overcast, although the temperature was already climbing.

Nick rolled onto his chest and pulled a pillow over his head. The extortionate price of drinks at the Crypt had saved him from the hangover he probably deserved. He lay for a while, trying to go back to sleep, until he heard Jess calling his name. He dragged the pillow off his head. Sally was telling Jess not to wake him, but Jess was taking no notice. She was standing directly outside his door, ordering him to get out of bed.

He got up and pulled on a pair of shorts and walked across the worm-eaten cypress floorboards. He opened the door and looked down. His mouth felt dry and metallic. ‘Jess,’ he grunted. ‘What can I do for you?’

She reached for his hand and tugged him towards the stairs. ‘There’s a dog outside. It won’t go away.’

Nick shrugged.

‘Mummy says it’s been sitting there all night. She heard it crying.’ Jess frowned.

‘Dogs don’t cry, Jess,’ Nick said reassuringly, although he knew it wasn’t true. Dogs cried, just as men cried.

‘Mummy says we’ve got to ring the dog catcher and he’ll come and take it away.’

‘That sounds like a sensible idea.’

‘I don’t want the dog catcher to take it away.’

Sally was standing in the hallway, studying the dog through the security grille. It was the greyhound that had followed Nick down Cleveland Street in the early hours of the morning.

‘I can’t see a collar,’ said Sally. ‘I suppose that means it’s been abandoned by its owner.’

The difference between dog-lovers and dog-tolerators, Nick knew, was in the pronoun: dog tolerators, like his father, habitually referred to them as ‘it’, whereas dog-lovers, like his mother, always gave them a gender. Jess was instinctively a dog-lover but, at three, was under the grammatical spell of her dog-tolerating mother.

Gingerly, Nick descended the stairs. ‘Come on, Jess. Let’s have a look at him.’

‘Don’t you go near it, Jess,’ said Sally. ‘It might bite you.’

‘I don’t think he’s a biter,’ said Nick. The dog’s ears were down; it looked more anxious than aggressive.

‘How can you be sure?’

‘I’ve seen this dog before. Last night. In the park.’

‘You mean you brought it home?’

‘God, no. I thought I’d got rid of him.’ Nick squatted down beside the animal. ‘He must have followed me.’

‘It’s a greyhound, isn’t it?’

‘An arthritic greyhound,’ said Nick, patting the animal’s sleek skull. ‘But I’d say it’s been a few years since he’s chased any rabbits.’

‘I’ll ring the pound,’ said Sally. Then, ‘I can’t. It’s New Year’s Day.’

‘Let’s give it some milk,’ said Jess.

Nick laughed. ‘Dogs don’t really drink milk, Jess. But I’m sure he’d like some water.’

The greyhound watched Nick, as though sensing its fate lay in his hands.

‘It wants to come inside,’ said Jess.

Sally glanced at Nick, then at the dog. ‘Take it through to the backyard. I suppose it can stay there till we’ve decided what to do with it.’

Nick trotted the greyhound down the hallway and through the kitchen and out into the vine-smothered concrete rectangle described by the agent who’d sold Sally the house as an ‘innercity entertainer’s paradise’. Then he took a cereal bowl from the sink and filled it with water and placed the bowl between the dog’s front paws. While Jess stood sentry at the back door Sally asked, ‘How was the wake?’

Nick thought for a few moments before answering. ‘Weird,’ he said at last. ‘Something about it reminded me of the Borgias.’

‘Sounds interesting. I wish I’d been invited.’

In the two months he’d been sleeping, as a friend/tenant, in Sally’s spare bedroom, Nick had become accustomed to these casual inquisitions. He wasn’t sure what they meant, or if they meant anything at all. He had known Sally since before she and Randy had started going out. Somewhere in the dim and distant past Nick could picture Randy, in black leather trousers, waiting for her at midnight outside the Star with a cigarette in his mouth and two motorcycle helmets under his arm. He’d observed, from one side only, the fireworks of their separation. It was obvious to Nick that, whatever Randy had or hadn’t done, deep down Sally still hoped they could get back together again. Sally was clever and funny and attractive. Nick had fancied her from the first time he’d laid eyes on her. But he didn’t want to be the one to prove to her that she was still in love with Randy.

‘It was for that friend of yours who committed suicide, wasn’t it?’

Nick patted his pockets for cigarettes. Sally didn’t like him smoking in front of Jess but it made him feel better to know where they were, to know he could light one if he had to.

‘He fell off a cliff,’ he said. ‘I’m not sure it was suicide.’

‘Oh.’ She waited for him to elaborate. When he didn’t she asked, ‘What was it then?’

Nick shrugged. He remembered the look on the faces of the two he’d recognised from St Dominic’s—as if they knew they were untouchable. ‘My guess is it will be an open finding.’

‘I wasn’t asking you about the finding.’

They stared at each other for a while.

‘You should have stayed in with us and watched the fireworks on TV,’ said Sally, changing the subject. ‘They were better than last year.’

Last year Nick had gone to see the fireworks with Carolyn. All he remembered was the argument they’d had on the bus on the way home.

‘There was a riot on Bondi Beach,’ said Sally. ‘Mostly English backpackers, according to the radio. They were fighting pitched battles with the police outside the Pavilion. It sounded pretty ugly.’

Nick picked up the paper—having the Daily Star delivered free every morning was one of the few staff benefits that hadn’t been axed in the last round of cost-cutting. The front page was filled with pictures of fireworks bursting over the Harbour Bridge. Nick turned to page three. There was nothing about British hooligans running amok on Bondi Beach. ‘So where’s this riot, then?’

‘It must have happened too late for the second edition. Rioters have no respect for deadlines.’

Compared with previous years, the harbour celebrations had gone off quietly. The Star had photographs of two policemen dancing with revellers in The Rocks, and of a police horse wearing a party hat. But

the new year had delivered its usual list of casualties: victims of drunken brawls and exploding fireworks; a late-night fisherman swept off the rocks at Garie Beach, a middle-aged man killed in a hit-and-run in Randwick; a mother and child missing from a yacht in Pittwater.

Sally glanced out of the window. ‘Do you think it’s hungry?’

‘The dog? Probably.’

‘What do dogs eat?’

‘I thought you were going to ring the pound.’

‘I am. But it’s a public holiday, remember? We can hardly starve it until tomorrow.’

‘There’ll be something at the shop,’ said Nick, looking for his wallet. ‘I’ll go and buy him something.’

‘It’s a she.’

‘Sorry?’

‘The dog you seem to know so much about. It’s a she. Only a minor detail, I know, but I thought you might have noticed.’

Nick took out his cigarettes. ‘Minor details often escape me.’

In the old days, when Sydney still had rival afternoon papers, there were two hotels on neighbouring corners of Broadway: the broadsheet Herald journalists patronised one and the tabloid Sun hacks crowded into the other. At night, groups of printers stood around a spluttering brazier on the wedge-shaped island in the middle of Wattle Street. Nick’s father had worked at the Sun, in the circulations department. Nick remembered him coming home each evening and slapping down his free copy of the late edition on the kitchen table, as if it was his own byline on the front-page splash.

Walking along Abercrombie Street towards Broadway, Nick caught the pungent whiff of fermenting hops from the Carlton brewery. While he waited for the traffic lights to change, he watched a semitrailer loaded with giant rolls of newsprint backing into the Herald ’s receiving bay. In a couple of years the presses would move to a greenfields site out west and the area would begin its metamorphosis into a pseudo-village of red-brick townhouses and warehouse conversions. But for the time being the newsprint kept coming, arriving in rolls and departing in bundles. The pedestrian light flashed green as the semitrailer’s red cab withdrew, like the head of a tortoise, into the receiving bay.

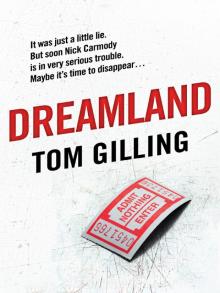

Dreamland

Dreamland