- Home

- Gilling, Tom

Dreamland Page 3

Dreamland Read online

Page 3

Nick wasn’t due at work until six. Emerging from the pedestrian tunnel, he climbed Devonshire Street and turned left into Crown, retracing his walk from the previous night. He knew where he was going but not why. He’d seen Danny off his face at the club, and he’d seen Danny’s car, abandoned but recently driven—presumably by Danny. What did he hope to gain by knowing more?

He kept on walking. Crown Street on Sunday evening was mostly deserted. He crossed the road and walked another couple of blocks. A lime green kombivan was illegally parked at the entrance to the cobbled lane where he’d seen Danny’s car. An acrid smell caught his nostrils: the smell of scorched metal.

Two teenagers in jackets and beanies were huddled beside the kombivan doing some kind of deal. Nick looked past them into the lane—and saw the charred body of the metallic blue Audi TT standing in a puddle of oily water. He hesitated a moment before approaching.

Amid the incinerated wreckage it was easy to see the empty space below the dashboard where the sound system had once been. A crystalline mound of toughened glass fragments lay on the back seat, just inside the door, although the front and rear windscreens had clearly been blown outwards when the fuel tank exploded. Somebody had broken into the Audi by smashing a side window and then stolen the stereo. Either the thief or someone else had set the car alight.

Tuesday was Sally’s day off. She and Jess had spent the morning splashing each other in the kids’ pool in Victoria Park. Nick, meanwhile, was doing his best to bath the dog in the laundry sink.

At the sound of the animal barking, Jess came running down the hall. She stood in the doorway and said, ‘Mummy’s wet her pants.’

Nick was still getting used to the room-silencing confessions that could fall from the mouth of a three-year-old. ‘Really?’

‘She did it at the pool.’

‘That’s a shame.’

‘I seed her do it.’

‘Saw,’ said Nick.

‘I sawed her do it.’

‘I don’t know what she’s telling you,’ said Sally, shutting the door behind her.

‘I don’t think you want to,’ said Nick.

‘Whatever it is, it’s not absolutely necessary to believe it.’

‘That’s what I was hoping.’

She stopped at the entrance to the kitchen. Nick had put too much shampoo in the water and the cracked linoleum floor was covered in suds. ‘Can I ask what you think you’re doing?’

‘I think I’m washing the dog.’ He paused. ‘I might be washing the floor.’

‘Why?’

‘Why what?’

‘Why are you washing the dog?’

‘She’s been living rough. She needs it.’

‘I thought we decided you were going to ring the pound.’

‘I thought we decided you were.’

Jess crouched down in front of the greyhound and said, ‘You mustn’t get suds in his ears.’

‘She’s a girl dog, Jess,’ said Nick. ‘And I’m being very careful not to get suds in her ears.’

‘I don’t like suds in my ears,’ said Jess.

‘How are you going to rinse it?’ asked Sally.

Nick stopped lathering the dog’s coat and wiped his hands on a towel. ‘I haven’t thought that far ahead. Maybe a hose in the yard…?’

Sally’s eyes narrowed. ‘Are you trying to soften me up?’

‘Why would I try to do that?’

‘Jess knows I don’t have time to look after a dog. I’ve promised her a guinea pig when she’s five.’

‘A guinea pig?’

‘When she’s five.’

‘Well, that’s something to look forward to.’ He smiled doubtfully at Jess. ‘Isn’t it, Jess?’

Sally frowned. ‘I wouldn’t expect you to know this, Nick, but three is generally considered too young to appreciate irony.’

‘What if I looked after her?’ Nick suggested. ‘After all, I was the one she followed home. If it doesn’t work out, I’ll ring the pound.’

Sally studied him, as though trying to identify the subtle physical change that signalled the transformation from unencumbered single urban male to domesticated dog-owner. ‘Is this because of Carolyn?’ she asked.

‘Carolyn never let me hose her down in the backyard,’ Nick said.

There was a long silence.

‘She won’t sleep in the house,’ said Nick. ‘I’ll buy a plastic kennel.’

‘I suppose you’ve given it a name.’

‘I haven’t. But Jess has. She wants to call her Fred.’

She smiled at Jess. ‘Fred isn’t really a girl’s name, darling.’

‘She’s not a girl,’ said Jess. ‘She’s a dog.’

It was Thursday evening. Nick was struggling to think of a clever headline for a wire story about an alligator running amok in the suburbs of Tupelo. The tagline at the bottom was from the Daily Mississippian. What on earth, Nick wondered, was the Star doing reprinting stories from the Daily Mississippian—in fact what was anyone doing reprinting stories from the Daily Mississippian? Once upon a time the Star had taken its international news from the New York Post, London’s Daily Mirror; sometimes even the tacky Bild Zeitung; now it was filching paragraphs from the Daily Mississippian and the Waco Tribune-Herald.

He skim-read to the end. Most of the jokes that sprang readily to mind for a rampaging alligator story were already there in the copy. As a last resort Nick knew he could always steal the best joke and delete it from the story. But Jerry Whistler, the chief sub, had read the raw copy and would know straight away what he’d done. Jerry was one of the few people in the newsroom Nick found it hard to get along with. And Jerry was one of Sally’s drinking buddies. There was a photograph of the two of them on Sally’s fridge, hamming it up a couple of years ago on the subs’ Christmas cruise. How did these things happen, Nick used to ask himself, as he watched Jerry Whistler hammering away at his keyboard like some demented church organist. How could Sally be friends with both of them?

As if he knew what Nick was thinking, Jerry looked up from his screen. Jerry had a lazy eye. To compensate he tended to squint with the other, screwing up the left side of his face as though taking aim through an imaginary gun sight. The wire basket on top of Jerry’s computer screen was empty, which meant all that night’s foreign stories had been assigned. For most of the past hour Jerry had been scrolling idly through the local news directory, pretending to be busy, when all he was doing was saving himself the trouble of having to read the paper in the morning.

‘Looks like your mate Grogan has got himself in a bit of strife,’ he said.

Nick could see Jerry Whistler waiting for him to react.

‘Let me guess,’ he said. ‘The Crypt has been raided again. Grogan’s been watering the beer.’

‘Not quite. It seems that young Danny has been a naughty boy behind the wheel.’

Nick felt a shiver go through him.

‘New Year’s Eve,’ said Jerry. ‘A camera caught him doing ninety down Moore Park Road.’

‘Who got the story?’

‘Flynn,’ replied Jerry.

It usually took at least a fortnight for a speeding notice to grind its way through the system. But Danny Grogan wasn’t your ordinary speeding driver. If Flynn had the story then someone in the police media liaison unit must have been shooting his mouth off. But how had the police found out? Fixed speed cameras were the responsibility of the Roads and Transport Authority. The police only became involved if the notice was challenged and the matter went to court. Danny Grogan was a prize scalp. Someone had spotted Danny’s name and made a few calls.

All Nick knew about Michael Flynn, the new crime reporter, was what he’d read on the staff noticeboard: Flynn was a lawyer who’d been a political adviser to the New South Wales police minister before taking a 75 percent pay cut to join the Star, and that he was fluent in Mandarin. Fifteen—even ten—years ago a Daily Star reporter was borderline overqualified if they knew how to use an apostrophe and

could name the prime minister of New Zealand. Flynn would be editor before he was thirty-five. Nick called up the story and read it as he waited for the foreign page proofs to arrive. At 10.27 p.m. on New Year’s Eve a metallic blue Audi TT with the registration number CR1PT had been caught by a speed camera doing ninety-three kilometres an hour on Moore Park Road.

The rest of the story—another ten paragraphs and a selection of incriminating pictures from the files—consisted of a potted summary of the troubled life of Danny Grogan, including a list of previous driving offences. Nick didn’t have to read the list to know that it was only eighteen months since Danny had been caught drink-driving outside the Bat and Ball Hotel. Thanks to some expensive legal representation Danny had escaped with a suspended sentence but the magistrate had made it clear that another conviction would mean jail.

Flynn’s information sounded good but none of the quotes were attributed, which meant that whoever had spoken to Flynn knew they were breaking the rules. At this time of night, as Nick knew only too well, it was almost impossible to reach anyone on the phone. You checked as many details as you could and either ran with what you had or held off and risked a bollocking at the morning news conference when the story turned up in the Herald.

Still, Nick knew a few things that Flynn didn’t. He knew, for a start, what state Danny Grogan had been in on New Year’s Eve. And, for what it was worth, he knew that Danny wasn’t alone that night. Not that he intended to share that information with Flynn. The whole thing looked suspiciously like the sort of off-the-record media stunt that had got the New South Wales police into trouble over the years. It reminded Nick of the choreographed drug swoops and stage-managed arrests so adored by TV news bulletins—and so skilfully exploited by defence barristers when the matter came to court.

In dealing with the police it was important, Nick had discovered, never to underestimate their capacity for duplicity. Experience had taught him to follow a simple rule: assume the police have something to hide (which is not necessarily what they are hiding) and ask questions accordingly. Michael Flynn, for all his fluent Mandarin, had only been the Star’s crime reporter for a few weeks—not long enough to have developed an instinct for when the police media unit might be over-selling a story.

The storm broke shortly after Nick got home from work. It began as a fierce, dry wind rattling the windows in their frames. Then it stopped. Thunder crackled in the distance but it seemed to be moving away, not coming closer. The noise Nick heard next was like a car wheel spinning in gravel. It erupted out of nowhere. Then there were lumps of hail bouncing off the tin roof. The dog was barking in her kennel. Through the gap beneath the door Nick saw the landing light go on. He heard Sally go into Jess’s room. If he knew anything about Jess, it was her mother who would be more frightened.

He thought about Danny. If he’d been stopped by a booze bus rather than picked up by a speed camera, the police would have found out he had the contents of a chemistry lab coursing around his system. Things could have been a lot worse for Danny. But they were bad enough.

Outside, the dog was howling. Lightning flashed behind the curtains. Nick went downstairs, slipped the bolts at the top and bottom of the kitchen door and whistled to the dog. Bounding out of the darkness, the greyhound shot past him, skittering sideways across the linoleum floor until it bounced with a hollow thud off the pantry door. Nick wondered what to do next.

Wondering what to do next was something Nick found himself doing a lot these days. Not about Carolyn: that was over. Maybe they would come out of it as friends. Nick didn’t mind the idea of giving it a try once the dust had settled. No, wondering what to do next was about more than finding someone to replace Carolyn. It was about finding someone to replace the person he’d been while he and Carolyn were together. That person already felt oddly remote. Perhaps it had something to do with the amount of time they had been together. Before Carolyn, Nick’s romantic history had been strictly short-term. He had friends at the paper who’d met, married and divorced within the space of eighteen months. It was going to take some time for him to adjust to not being the person he was.

The greyhound inclined its slipper-shaped skull to one side, its eyes bulging hopefully, and after a moment’s hesitation Nick followed the animal upstairs, where it spent the night curled up among the shoes at the bottom of his wardrobe.

The phone was ringing: in Nick’s mind. It seemed to ring for hours before a familiar voice swam up from the depths. ‘Telephone, Nick. For you.’

His alarm had failed to go off, because Nick had failed to set it. He stumbled downstairs and picked up the receiver.

‘Nicolas?’

He didn’t recognise the voice.

‘This is Harry Grogan. We met some years ago.’

‘Yes,’ said Nick, vaguely remembering a surreal encounter outside the huge wrought-iron gates of the Grogan mansion.

‘Have you read the papers?’

‘No,’ said Nick, although he guessed what the call was going to be about.

‘Danny’s been caught speeding.’

Nick didn’t say anything. As far as driving offences went, Danny was on his last life.

‘I’d like to talk to you, Nicolas. See if there’s anything that can be done.’

‘What Danny needs is a lawyer, Mr Grogan.’

‘I’d still like to talk to you.’

There was a sharpness in the older man’s voice, a hard edge beneath the courtesy that Nick had heard many times before: at shareholder meetings, as Grogan brushed off annoying questions about directors’ remuneration; at press conferences, while slapping down half-hearted interrogations about zoning restrictions or endangered butterflies. Harry Grogan was accustomed to being obeyed.

‘I really don’t see how I can help,’ said Nick.

‘I’ll send a car for you,’ said Grogan.

‘I’m working this afternoon.’

‘This won’t take long, Nicolas.’

‘All right. I suppose…’

‘I knew you wouldn’t let me down.’

Nick was just getting into the shower when there was a knock at the front door. Sally’s voice shouted up the stairs, ‘Someone for you, Nick.’

Harry Grogan must have sent the chauffeur even before picking up the phone. Nick wondered how Grogan had known where to find him. Someone on the switchboard must have broken the rules by giving out his address. He had asked for a silent number after a series of anonymous calls to the flat he’d shared with Carolyn in Elizabeth Bay. For a while the police had put an intercept on his phone at work. The anonymous calls stopped without Nick finding out who was behind them or what they were about—or whether they were even intended for him. For all he knew, the calls could have been meant for Carolyn. As a criminal lawyer she had no shortage of intimidating clients. But Nick had stopped being the Star’s crime reporter a year ago. Now he was a subeditor on the foreign news desk. Subeditors on the foreign news desk didn’t need protecting from anyone— except themselves, maybe.

Harry Grogan’s chauffeur was tanned and stocky, with an inverted saucer of black hair on the crown of his head that reminded Nick of the black-helmeted birds he saw wading in the ponds in Centennial Park. His broad shoulders and bulging biceps looked like the product of long daily workouts in front of a mirror. Nick guessed he was in his late fifties or early sixties— too old, he couldn’t help thinking, for a body like that.

Sitting there, half wet from his half shower, Nick soon realised that the Jaguar was heading not for the marble cylinder beside the botanical gardens that formed the headquarters of Grogan Constructions, but for the slip road to the Harbour Bridge.

‘Where are we going?’ he asked. ‘I thought I’d be meeting Mr Grogan in his office.’

‘Mr Grogan is at his vineyard today.’

‘I start work at five.’

‘Mr Grogan has instructed me to have you back here by 4.45.’

Nick knew all about the vineyard. While Grogan Constructions was busy r

ipping up 100-year-old Moreton Bay fig trees, Danny’s father used to have himself photographed among the trellises in his olive-green gumboots and Driza-Bone coat. With its organic vineyard and rammed-earth tasting room, and its ostentatious donations to WWF, Grogan Estate Wines was a badge of environmental respectability for a company that stood for its opposite. Harry Grogan had even succeeded in luring a busload of wine journalists to the Hunter Valley to watch him roll up his trousers and crush grapes between his toes. That was the thing about Grogan: he knew that if you told one story well enough, journalists would eventually stop asking you about all the other stories.

The windows of the Jaguar were so heavily tinted that it could have been evening outside. Harry Grogan’s cars had always been dark—and English. Nick remembered the claret-coloured Daimler that waited for Danny outside the school gates on the rare evenings when his presence was required at home. And he remembered Danny’s little jokes about the ‘weirdo’ chauffeur who wore leather driving gloves, even in the middle of summer.

‘Nice gloves,’ said Nick.

The chauffeur said nothing but reached across to switch on the radio.

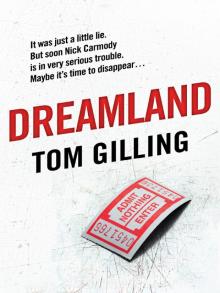

The stock market was falling but Grogan Constructions was having a good morning, up nearly 5 percent in the first few minutes of trade. There was speculation in the Herald that Harry Grogan was ready to sign a deal with the Consolidated Gaming Company of Illinois to build a Dreamland casino in Las Vegas and, at the same time, that Grogan was close to reaching agreement with a Dutch company to develop a luxury Dreamland resort on the French Polynesian island of Bora Bora. Before long, the company boasted, there would be a Dreamland on every continent.

Harry Grogan was a master at bypassing the orthodox institutional channels and talking straight to the media, putting the day traders in a frenzy for a session or two while the stock exchange timidly sought ‘clarification’ of the rumours.

Dreamland

Dreamland